June 2025

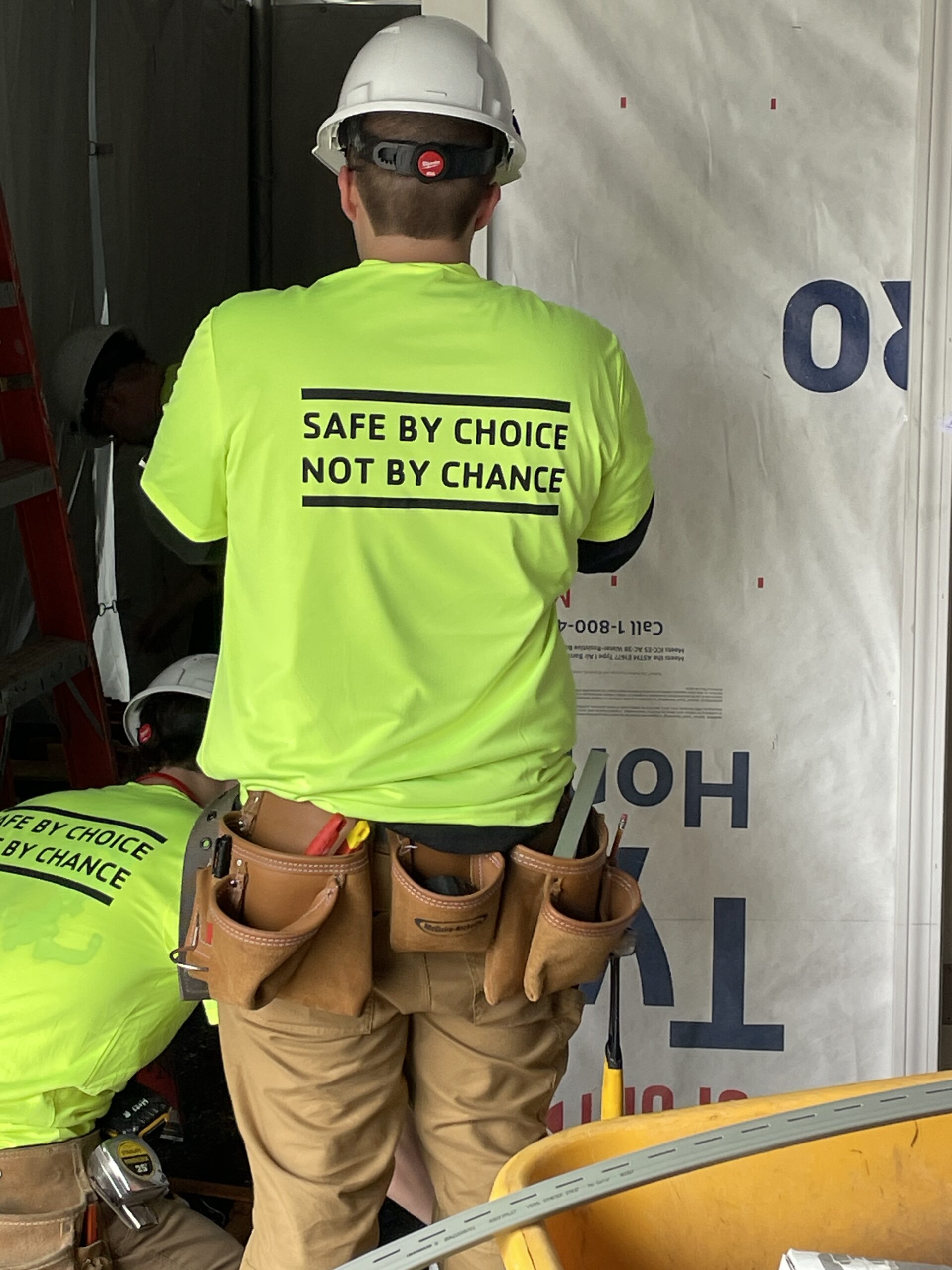

Last month I wrote about the Skills USA competition where I saw high school students who are preparing to go into the trades demonstrate what they can do. Through them, I got a glimpse of the future, which left me feeling optimistic.

For today’s newsletter, I’ve made a 180 to look at the past. In particular, I’m looking at Mary Patten, the first American woman to command a merchant ship. Her story leaves me in awe.

Mary Ann Brown was born in Boston in 1837. At the age of 16, she married mariner Joshua Patten who, only 25 himself, was given command of a clipper ship named Neptune’s Car. She was a big ship – 216 feet long, with a displacement of 1,616 tons. With an extended bow and the greatest beam further aft than was typical, she was an extreme clipper, built for speed. Her three masts carried multiple sails, some of which spread 70 feet wide.

Neptune’s Car, painting by O.E. Potter, Naval History and Heritage Command, courtesy of Marine Historical Association, Inc., Mystic, Connecticut

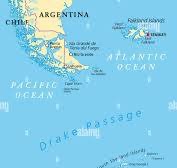

Soon after they married, Mary joined Joshua on a voyage around the globe, to San Francisco, China and London, before returning to New York. Rather than sit idly, she spent hours with a sextant and compass learning celestial navigation and studying the many other aspects of seamanship. On July 1, 1856, Mary and Joshua departed on a second voyage with a cargo of mining machinery destined for the California gold fields. To reach San Francisco from New York, they headed for Cape Horn, at the southern tip of Chile. There they encountered a reality worse than expected, even though they were well aware of the Horn’s reputation for bad weather and high seas.

Westward progress was nearly impossible, but Joshua persevered. After more than a week battling extreme conditions, he became seriously ill and took to his bunk. The first mate, who normally would have assumed command, had been confined to his cabin as punishment for dereliction of duty. The second mate was illiterate and unable to navigate. That left Mary the most qualified to take command.

During her first days as captain, the first mate made a bid to be released from his punishment, a move Mary rebuffed without hesitation. He also incited a small contingent of seamen to threaten a mutiny, but she faced them down and won the crew’s unanimous support. Then she made a bold decision. Rather than trying to head west against strong winds and high seas, she changed course and headed south, towards fields of icebergs that clustered near the South Pole. Eventually, she found a refuge of calm and set a new course for San Francisco.

Four and a half months after leaving New York, they arrived safely, Mary still in charge and Joshua still dreadfully ill. Ashore, she confessed she had not changed her clothes for 50 days, so busy had she been with the duties of command and nursing her husband. After a brief period of rest, she and Joshua boarded a steamer back to Boston. By then, he had lost his sight and hearing, and much of his cognitive abilities. He died the following year in an asylum in Somerville, an early incarnation of today’s McLean Hospital, now in Belmont, Massachusetts.

Although the tragic circumstances that gave rise to Mary’s taking command were unforeseen, at least one woman had, in a way, envisioned it. Margaret Fuller, in her 1845 opus Woman in the Nineteenth Century, mused that if societal barriers were removed, the world would see what women could really do. “[I]f you ask me what offices they will fill: I reply – any. I do not care what case you put; let them be sea-captains, if you will.” To me, this sounds as though she was naming the most outlandish thing she could think of for a woman to do. But a decade later, Mary did it.

And get this! Not only was Mary 19 years old and a first time captain, she was pregnant throughout the voyage. Less than a month after returning to Boston, she gave birth to a son. You know that famous quote that Ginger Rogers did everything Fred Astaire did, but backwards and in high heels? I can’t stop thinking it was really meant for Mary.

In September, I’ll be interviewing and riding along with a woman who works on the water today, piloting huge container ships in and out of Houston, Texas. The 309 million tons that pass through Houston annually make it the largest port in the country, in terms of tonnage. In my mind, this pilot whom I will meet is a descendant of Mary Patten, one in the family of female merchant mariners.