February 2024

Six degrees of separation. That’s the title of a play and a movie. A phrase we say when a surprising connection pops up. Also a network theory studied by social psychologist Stanley Milgram in the 1960s, and again by sociologist Duncan Watts in the early 2000s who, aided by computing power that hadn’t existed in Milgram’s day, wrote Six Degrees: The Science of a Connected Age. Today, network science is a part of academia that reaches into social, commercial, political and technological realms. Yet, even without any scholarly trappings, I had my own “six degree” experience when two strands of my writing unexpectedly came together.

I planned to start the year with research on Mother Jones, the labor organizer. After a slight delay in starting (thanks to an exploding chestnut), I did read a biography, autobiography and multiple web entries. Now, with pages of notes, I’m ready to draft a chapter of my book-in-progress.

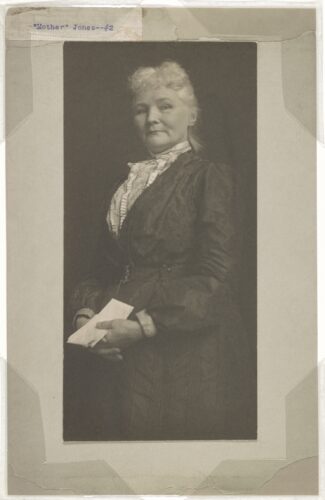

Mary Harris grew up poor in Ireland, emigrated during the potato famine, first to Canada, and then to the US, and ended up in Memphis where she married George Jones, an iron worker and union leader, and had four children. When yellow fever swept through the city, she lost her entire family. She became a dress maker in Chicago until fire destroyed her business and much of the city. After that, her sympathies for the working class came to the fore and she became a union organizer, crisscrossing the country to advocate for laborers and help them organize. “Mother” Jones became her new name, crafted to fit her emerging persona. She roused workers in many states across a range of industries but is best known for organizing coal miners in West Virginia, when armed conflict between mine operators and laborers raged. By 1901, she was “the most dangerous woman in America,” according to a West Virginia government attorney.

Mother Jones, 1902,

photo by Bertha Howell, Library of Congress

Around the same time, John D. Rockefeller was riding high with Standard Oil. His company controlled almost all aspects of the American oil industry, and it made him the richest man in the country. His portrait, painted by John Singer Sargent, was recently on view at the Museum of Fine Arts. When I wrote about the Sargent exhibit for my newsletter subscribers and for Arts Fuse, I didn’t mention the Rockefeller portrait because it didn’t really fit with the overall thesis of the exhibit, that Sargent dressed his subjects fashionably so he could memorialize their elite social status on canvas. For his portrait, however, Rockefeller dressed in a decidedly downscale manner, with serge paints and a dark jacket, a far cry from the haute couture worn by Sargent’s women, and the military uniforms, riding habits and even the red bathrobe sported by Sargent’s other male subjects. Rockefeller’s expression, too, seems low key, skeptical, even unhappy. Sargent didn’t agree with me and wrote to a friend that Rockefeller’s appearance was that of a medieval saint.

John D. Rockefeller, 1917, oil on canvas,

painting by John Singer Sargent

I never dreamed Rockefeller, an arch capitalist and anti-unionist, would converge with Mother Jones, a Socialist and radical union organizer. But they did, and the convergence gave me a thrill, to see two independent strands of my writing come together. It was six, or maybe fewer, degrees of separation.

By the early 1900s, Rockefeller had taken over the Colorado Fuel & Iron Company. Laborers were attempting to unionize, and they met with armed resistance from the company. A series of skirmishes, known as the Colorado Coalfield War, culminated in the Ludlow Massacre of 1914, where more than 20 people were killed, including the wives and children of striking workers. Following the massacre, Mother Jones met with “Oily John,” as she called him, and also with his son. Some reforms followed, but not enough for her. She denounced Rockefeller as the greatest murderer and thief the nation had ever produced. To her, he was no medieval saint, and no amount of philanthropy could atone for his anti-union sins.

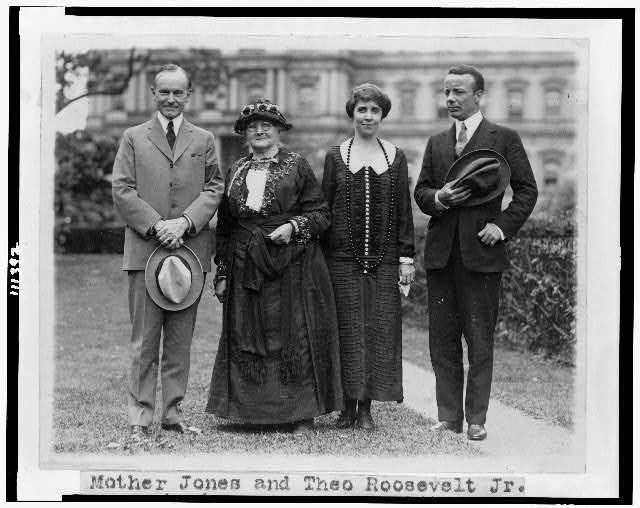

Maybe I should have anticipated that these diametrically opposed characters would meet. They were contemporaries, both engaged in the long struggle to define roles for corporations and workers. Mother Jones’s activism got her into Congressional hearings and the White House, and a meeting with Rockefeller was probably par for the course. (The photo at the top of this post shows her with President Calvin Coolidge, Mrs. Coolidge and Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. in 1924.) Still, I hadn’t known anything about her until recently, and had no inkling that someone like her would overlap with someone whose portrait was painted by Sargent. But discovering a connection like that makes writing fun.

On a separate note: Art enthusiasts have until February 11 to see the group show at Brickbottom Gallery in Somerville, featuring the work of five local artists. Here’s my recent review.