May 2024

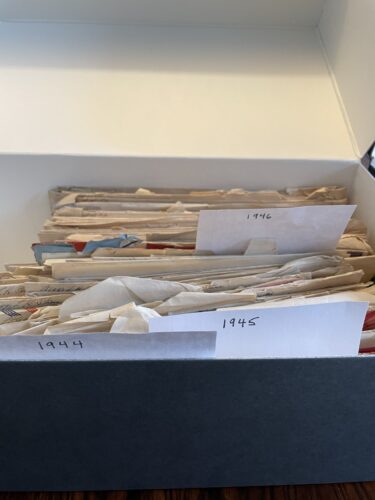

One day, several years before my mother died, she asked me to go into her attic and retrieve a box of letters. I found a decaying cardboard box crammed full of yellowing envelopes and brought it to her. “I want you to have these,” she said, explaining they were letters my father had written when they were dating, from late 1944 until August 1947. They were apart most of that time, my father onboard a Navy subchaser in the Pacific Ocean, then in Portland, Maine for his last Navy assignment as officer in charge of harbor traffic, next in Cambridge, Massachusetts for grad school, courtesy of the GI Bill, and finally in Biddeford, Maine for a summer job that lasted until the end of August when my parents got married. Throughout this time my mother worked for IBM, first in Endicott, New York for training at corporate headquarters, then in Worcester, Massachusetts, her base for serving regional clients.

I took the box of letters home and randomly pulled out one. There was my father musing about how far he and my mother should proceed with physical intimacy before marriage. I quickly stuffed the letter back into the box, consigned the box to the back of my closet and didn’t touch it again until last summer, more than 30 years later.

When I pulled out the box, I was no more interested in my parents’ sex life than before, but something had changed. That something was me. I knew I soon would be the age my mother was when she died. And although she hadn’t given me any explicit instructions about the letters, I had been an irresponsible custodian – not reading more than one letter in 30 years, not telling my brother about them, and not liberating this piece of family history from my closet and passing it on.

In August, I began to read. Soon I saw that pre-marital sex was a very small part of what my father wrote about, and I needn’t have been afraid. I briefly considered transcribing the letters, but that was too daunting a task. I decided instead to select sentences from each and copy them into a word document, chronologically arranged. My goal wasn’t to summarize each letter, only to capture elements that resonated with me. Many did.

Sometimes my father wrote about the gown my mother had worn to a dance they attended when he was home on leave. More often he wrote about life on the ship, books he was reading, music he liked, the stray dog another sailor brought on board, history classes in grad school, and jobs he planned to apply for when he got his degree. He also wondered whether he should go to law school.

Mostly, my father came across as the person I knew. His love of books was very familiar. When I was a child, I used to look at his books on the shelf, each with a handwritten note of when and where he had acquired it. I recounted that memory in the introduction to my book, They Called Us Girls. But now I was reading his opinions of books that hadn’t been on the shelf. Look Homeward, Angel, for example. Last year Andrew and I visited the Thomas Wolfe Memorial in Asheville, NC where we bought a copy of Look Homeward, Angel. We both read it last summer and, within days of finishing the book, I came across a letter, sent from somewhere in the Pacific Ocean, where my father praises it and recommends it to my mother. If only I could unwind time and have that conversation.

The man I knew growing up was intellectually curious, disciplined, stoical and sometimes cynical. He was also an active participant in household duties (aside from cooking). That’s how he comes across, even telling my mother that he daydreamed about them doing the dishes together. But, as a 24-year-old man in love with a woman, he revealed another side too. Repeatedly he told my mother that he liked the color of her dress, that her new hair style was becoming, that he dreamt of her every night and longed to put his arms around her. Romantic, sappy stuff that later was either kept private between my parents or pushed aside by a full-time job, volunteer work, kids and a busy household.

The project took me away from my other writing, but I wanted to do it. Not only was there a lot that resonated with me, but my brother had a significant birthday coming up, and the excerpts I was compiling were to be my present to him. I knew he would find resonance too. But working with the letters was also relevant to my work. I’m always curious about how people get to be who they are as adults. That is what I was trying to find out when I interviewed women for They Called Us Girls. Now I’m embarking on a second book project. These women will be younger and working in the manual trades, but the question – how we develop into our adult selves – remains. As I read my father’s words, I saw the makings of the man I knew.

The compilation of excerpts is now printed and shared with my brother, and the letters are stored in new, acid-free boxes. I know some of you have published books about your own family history, and probably others are exploring it informally, without intent to publish. I will think of you as you wrestle with the labor involved and the emotions that surface.