November 2024

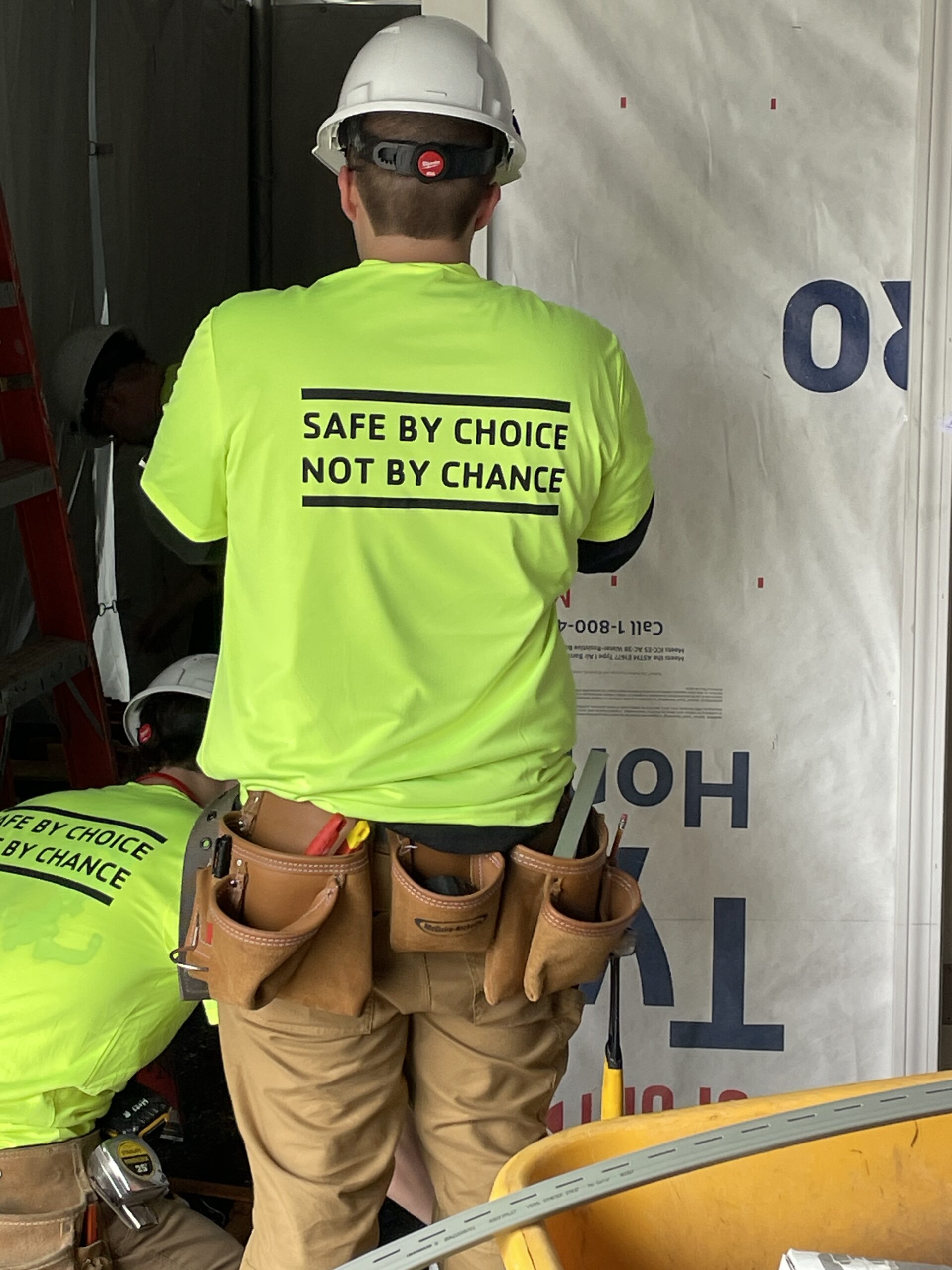

I’m recently back from West Virginia, my third trip to that state for book research. This time I accompanied Alison, whom I had interviewed previously, to a public school near the Kentucky border where her company is installing solar panels. Alison is a project manager with Solar Holler, and I wanted to see how she goes about her day, simultaneously managing crews at four different work sites. She’s the sole woman on the operations side of the business, together with fifty male electricians.

On an earlier trip I had interviewed Bonnie, a retired coal miner. Bonnie went into the mines in the late 1970s, soon after women were first allowed to work underground. (Traditionalists claimed that women would bring bad luck into the mines.) Now I’m drafting a chapter that bookends what I learned about the role of women in the historic industry of coal mining and in the new, innovative solar power industry.

Coal mining is not an industry I knew much, or really anything, about before I met Bonnie. But her story was so interesting that I allowed myself to be captured by the undertow that Patrick Radden Keefe describes in his book Rogues: True Stories of Grifter, Killers, Rebels and Crooks. As Keefe writes, “I sometimes feel as if I could happily float away, following the research wherever it takes me.” I quite agree. Plunging into a compelling topic, even one with a tangential relationship to my current book project, is one of the pleasures of writing. Here are some highlights of what I learned in coal country.

In the spring, on the trip before this one, Andrew and I visited Beckley, a town in southeastern West Virginia, where an old mine is open to the public for exhibition purposes. For the ride in, we boarded a mantrap, the type of conveyance Bonnie rode every working day. She had said she was scared to enter the dark, dank underground space, but I was relaxed because I knew we would be underground for only a short time, without the blasting and digging that can cause cave-ins. Click below to watch the video.

After Beckley, we drove to the southwestern corner of the state to Matewan, where we learned about the mine wars. The mine wars were a series of conflicts that took place in the early 20th century between laborers who wanted to unionize and mine owners who would do anything to stop them – evict miners and their families from their houses, convince politicians and judges that union men were communists, and hire armed guards to police laborers’ every move. Also sanction violence. A fatal skirmish, known as the Matewan Massacre, occurred in 1920, and the Mine Wars Museum is now a tourist attraction in the town. Before visiting Matewan, I had learned some of the mine wars history from reading about Mother Jones, the labor organizer. Just as going into a mine brought Bonnie’s stories to life, being in the place where a seminal event occurred made the history more real.

You may know the superb movie Matewan, written and directed by John Sayles, starring James Earl Jones, Chris Cooper, David Strathairn, Mary McDonnell and others. The movie depicts the hardships coal miners endured and the violence they faced for attempting to unionize and, with one exception, closely follows history. The exception is that the movie was filmed not in Matewan but in nearby Thurmond, where no post-1920 infrastructure contaminates the streetscape. Even Thurmond’s stark, isolated railroad depot is straight out of the mine wars era.

At the far end of Matewan’s town center, we noticed a mural about two feet high that runs next to the sidewalk. Miners hoisting axes, crouched low inside a tunnel, brought up feeling of claustrophobia, even to us passersby.

While we, obviously visitors, studied the mural, a man approached and invited us into the local offices of the United Mine Workers of America. There we were introduced to union officials and to a graduate student who was organizing an archaeological dig. His team planned to excavate the area where striking miners, evicted from their company-owned housing, camped in tents at the time of the Matewan Massacre. They expected to recover household artifacts, things that would enhance an understanding of how miners and their families scraped by during the mine wars.

With West Virginians like Alison finding new and different ways to work, momentum seems to be shifting away from coal (a survey by West Virginia University reports about 1.2% of state citizens work in coal mining, compared to 8% who previously worked in the industry), but mining still figures large in many West Virginia lives. In a restaurant where we had lunch, one man told us, “When I finished high school, the only things to do were join the military or go into the mines. I went into the mines.” With that as his choice, his experience of the world is fundamentally different from mine, but that’s exactly why I enjoy the research. It takes me to people and places I never would find if I did not allow the undertow to carry me there.

A quick postscript – on my trips to West Virginia, I did not raise the subject of environmental degradation or carbon’s contribution to climate change. I did not want to create a barrier that might inhibit conversation about what I was there to discover. Those concerns are well covered in much of the literature, particularly Coal: A Human History, by Barbara Freese, former assistant attorney general for Minnesota. Freese writes brilliantly and her book is full of fascinating content.