August 2024

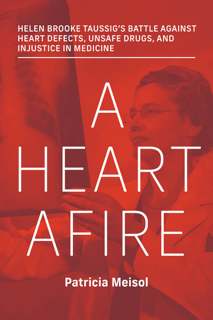

This month, I am thrilled to host a guest post by Patricia Meisol, author of A Heart Afire, a biography of Dr. Helen Taussig.

Patricia has been writing narrative non-fiction and investigative journalism for more than 25 years. For 16 of those years, she wrote for the Baltimore Sun, where she often profiled courageous individuals. A health policy expert, she spent five years developing finance policy for the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. She is one of the many talented writers I have met through Biographers International Organization; her website has more information.

Patricia’s book, A Heart Afire, is the story of Dr. Helen Taussig, a doctor who took a job none of her male classmates wanted. Infused with personal determination, she used her position to find a way to save dying children. Gracious but fierce, and an indefatigable worker, Helen Taussig had the idea of performing heart surgery on children, then a novel concept, which laid the groundwork for similar surgery on adults. In the second half of the 20th century, as technology replaced a doctor’s touch, she gained worldwide fame as a patient advocate and for her galvanizing role in the passage of US drug safety laws.

As we enjoy the month of August, Patricia gives us an insight into Dr. Taussig’s summer on Cape Cod and how it became a springboard for the physical and mental renewal she needed to continue her life saving work.

Stepping away

In her first years as head of an experimental children’s heart clinic, Helen Brooke Taussig restored herself by fleeing hot, muggy Baltimore in August for a few weeks to her family’s sprawling summer home in Cotuit, MA. But in the summer of 1934, despairing over dying patients and her own future, the sound of nieces and nephews playing joyfully on the beach disturbed her. The thought of returning to work depressed her. Instead of spending just a few weeks on Cape Cod, she stayed for five months, uncertain whether she would ever return to her clinic.

Helen hit many a wall in her 87 years, but this was her only near-breakdown. Ultimately, she did what she always did – devise a way around it. Graciously but firmly, she demanded additional staff for her clinic and, at her father’s suggestion, she moved to safeguard her mental and physical wellbeing. With an inheritance from her grandmother, she built herself a small cottage in Cotuit that would force her to take regular respites. The plan worked. By late 1935, at Johns Hopkins Children’s Hospital in Baltimore, Helen made the breakthrough that would establish her reputation as a master diagnostician. By 1944 she was in the operating room when surgeon Alfred Blalock built a new path for blood to the lungs in what became the first successful heart surgery. It was Helen’s idea.

I was drawn to writing about Helen, but not only because she was a doctor whose ideas saved thousands of so-called “blue babies” – children with heart abnormalities that deprived them of oxygen. I knew so little about hearts that to understand how they worked, I had to regularly sketch their parts, then tape them to the wall near my desk. No, I was interested in Helen because she succeeded so spectacularly in a man’s world, and I wanted to know how – and why. As I studied hearts and researched Helen’s life, I began to see similarities. Both had the capacity to develop alternate routes around blockages. In medicine, it’s called collateral circulation. Indeed, Helen came up with the idea to save blue babies after discovering that children with extra blood vessels lived longer.

Similarly, Helen developed the will to surmount obstacles beginning in childhood when, as a child with dyslexia, she was forced to find ways to unravel words on a page. She left beloved family in Boston to pursue her dream of becoming a doctor in Baltimore because Harvard wouldn’t admit women. Months into her job as head of the new children’s heart clinic, she lost the central tool doctors need to detect problems of the heart – her own hearing. In place of a stethoscope, Helen learned to “listen” to sounds of the heart with her hands on a child’s chest.

Like the abnormal hearts she treated, she had to work harder to survive. Adroitly, she drew oxygen from Cotuit to build a Cotuit-style house and gardens in Baltimore. That, combined with methods and data, and her own fame, allowed her to remain an ardent advocate for patients. Touch, she believed, brought her closer to her patients. They, in turn, empowered her.

Patricia’s book is available at your favorite bookstore or online at Bookshop.org and Amazon.

With thoughts of seasonal renewal in mind, I wish you a great rest of the summer, wherever you may be.

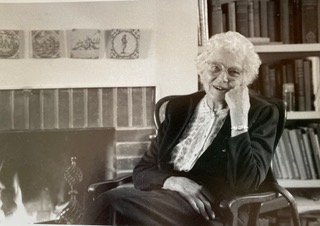

*Credit for the photo of Dr. Taussig goes to Polly Henderson Horn