January 2025

First, I have an invitation for those of you who will be in or around Boston on March 12. On that evening, I will be at Parkside Bookshop, the new bookstore in the South End, talking about They Called Us Girls: Stories of Female Ambition from Suffrage to Mad Men. With me will be Robin Foster, author of the recently released Grit & Ghosts: Following the Trail of Eight Tenacious Women across a Century. With both books about women who overcame barriers in the past, our conversation is timed to honor Women’s History Month. We would love to see you there.

Now, on to this. month’s newsletter, beginning with the sculpture pictured (above) titled “Homage to Women,” by Nico Kaufman, a Romanian-born artist who immigrated to the United States in 1951. The piece is installed at the Lowell National Historical Park where I saw it while doing book research. I was in Lowell to learn more about mill girls, the young women who labored in the mills in the first part of the 19th century and who the sculpture honors. I’m doing this research in connection with writing about a woman who works in a modern factory. I want to contrast her contemporary story with the historical context of women in manufacturing. As I learned, the manufacturing history of Lowell is significant, but that’s not where things began. As I recently learned, the industrial revolution in America began slightly earlier and not very far away, in Pawtucket, Rhode Island.

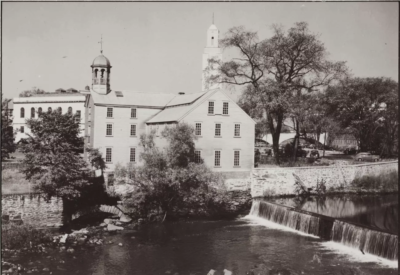

The Old Slater Mill (pictured above), part of the Blackstone River National Historical Park in Pawtucket, was a “manufactory,” to use the archaic term. A spinning frame powered by the river that runs just outside the door spun cotton into yarn which was then given to women who, with hand looms at home, wove it into cloth. A far cry from contemporary manufacturing, this was the first step in the American industrial revolution. And it was based on child labor. Ann Arnold, a ten-year-old girl, is generally considered to have been the mill’s first employee.

Samuel Slater was responsible for the spinning frame that Ann Arnold used. In 1778, a child of ten himself, he had become an apprentice in a textile mill in the English Midlands. England led the industrial revolution at the time and was desperate to maintain its preeminent position. British law made it illegal to copy or share the design of textile machinery, and workers in textile mills were forbidden to leave the country. But Slater was not deterred. Every day for the decade he worked in the mill, he saw a spinning frame and was able to memorize its design. In 1789 he sailed to America, a country then in its infancy with a brand new Constitution. He joined forces with two Rhode Island men who built the mill in Pawtucket and installed a spinning frame built to Slater’s specifications. By the end of 1790, ten or twelve children were working at the mill – Ann, her sister Eunice (age seven), her two brothers, and six or eight other children. Child labor was common in England. New England families, unable to sustain themselves with farming or artisanry, reluctantly adopted the practice, even though it was in conflict with the Jeffersonian agrarian ideal and the rhetoric of independence that had so recently inspired the break with England.

I took a tour of the Slater mill and saw a preserved spinning frame at work. One frame alone made it almost too loud to hear someone speaking. An entire factory floor would have been deafening.

Later I emailed with a park ranger about a follow up question. A history enthusiast himself, he was very helpful and pointed me to several resources, including the work of Gary Kulik, a historian who was curator of textile machinery at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History. With the help of the Boston Public Library and the Massachusetts State Library, I got access to Kulik’s PhD dissertation and one of his books on early New England mill villages, where child laborers and their families lived. Using meticulous research, Kulik brought together details about workers’ lives that transported me to New England as it existed not long after the Revolutionary War.

Ann Arnold worked in Slater’s mill for less than a year, according to company records; little is known about her later life. As the park ranger explained, even if she had been counted in a census, her name was most likely not recorded. Early census takers noted only names of heads of household, most often men.

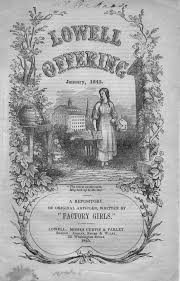

About 30 years after Slater’s initial step toward industrialization, the first mill opened in Lowell, with two significant innovations. One was the use of power looms that operated along with spinning frames. No longer would a factory give cotton yarn to women to be woven at home. Instead, all the steps of converting raw cotton into cloth would take place in the mill. Like the spinning frame, the power loom was invented in England. Also like the spinning frame, its design was memorized and replicated in New England, this time by Francis Cabot Lowell, a Massachusetts native. On this visit, the ranger ran several looms as a demonstration (pictured below). Even without all of them running, it really was deafening.

The second innovation pioneered in Lowell was the composition of the labor force. Instead of relying on children and some adults, the new mills recruited young single women from the New England countryside. Workdays were long and boarding house rules stringent but, by stepping out of domestic life on the family farm and into wage-earning life in the city, the mill girls took a big step toward opening their own and other women’s eyes to what could lie ahead.

Unlike Ann Arnold, many mill girls left a long trail through history. Some became labor leaders, organizing workers and strike activities; others advocated for the abolition of slavery or female suffrage. Many wrote about their lives and much of their writing is preserved in periodicals and books.

Textile production in the 18th and 19th centuries is not something I ever thought much about before now, but I probably should have. Both my grandfathers worked for the Saco-Lowell Shops in Maine, a manufacturer of textile machinery. They began working there about a century after mill girls first went to Lowell, but their company had historic links to that past. As I suspect is true for almost everyone, I just didn’t pay ask the right questions when I had the chance. But now, after visiting the two national parks, I have a better understanding of how the industrial revolution affected society. Seeing the original machinery operate in the old mills and imagining the experience of children and young women working at them for ten or more hours a day, six days a week, provided more insight than any history book I ever read in school.

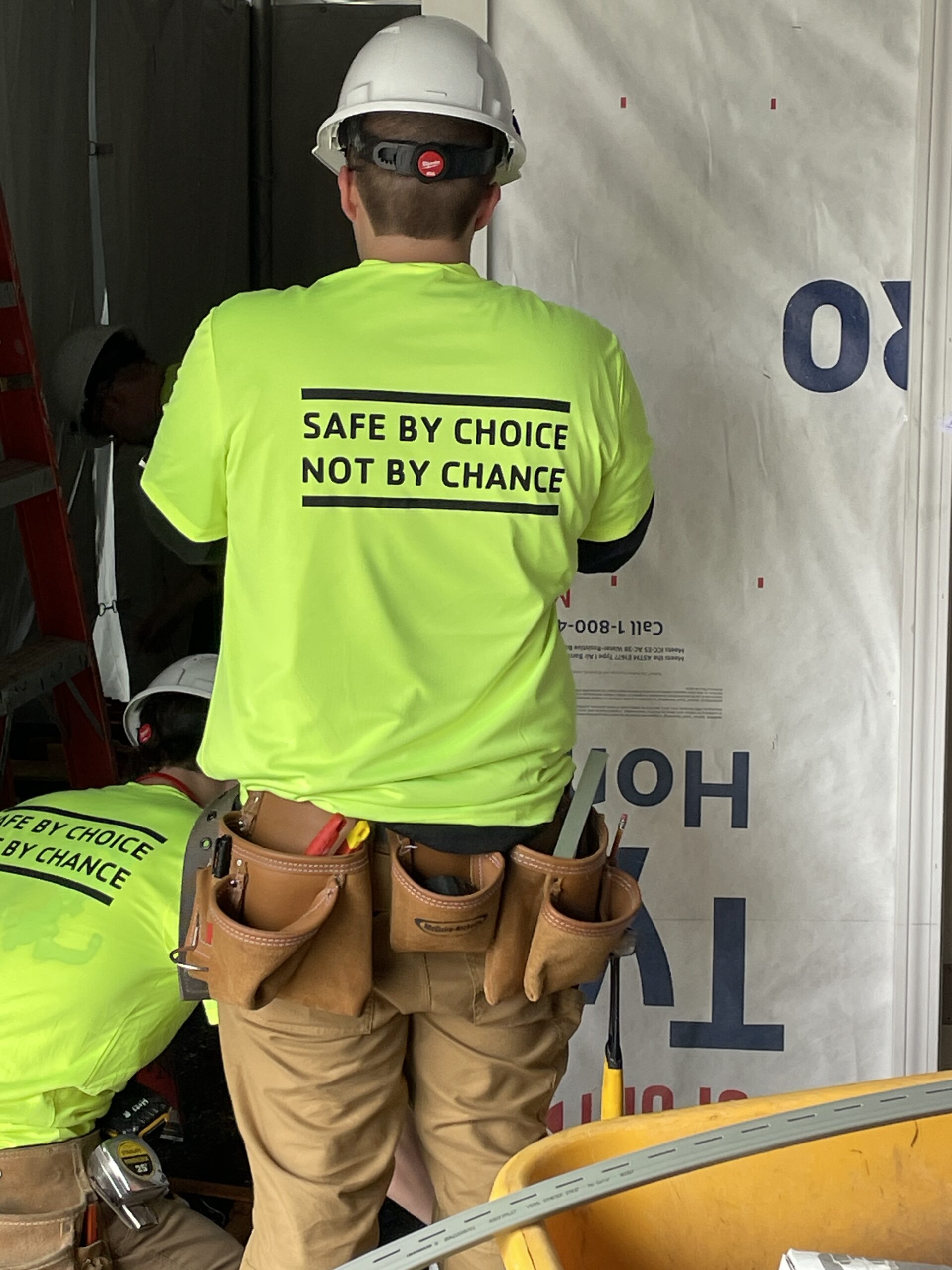

In my book, I want to cover the societal changes that occurred as the country industrialized, while also telling the story of women in the trades, including manufacturing, today. Much writing and revising lies ahead!