November 2022

Here we are on the cusp of turning back the clocks, which means I have to concede that summer is over. If you remember the July newsletter where I shared my overly ambitious summer reading plans, you won’t be surprised that I did not finish everything, not even close. But no matter. I wrapped up the summer with two happy events. In September our son James was married on a sunny, windy day in northern Vermont. The reception turned into a great dance party with delicious food, and Andrew and I are thrilled to have Lauren as our daughter-in-law. Four days later, we flew to Seattle to see the San Juan islands (by boat) and other highlights of the Pacific Northwest (by car and foot). Trees, mountains and rivers are undeniably majestic in that part of the country, but two museum visits were equally grand.

Makah carved sculptures

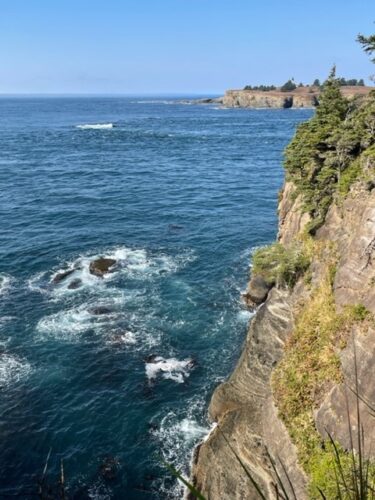

For millennia, the Makah tribe has inhabited the northwestern portion of Washington state. Living on the ocean’s edge, they hunted seals, sea lions, salmon and whales, and gathered berries and roots on land. Cape Flattery, the most northwesterly point of the continental United States, lies within their traditional tribal lands.

View from Cape Flattery

In 1970, a storm eroded a strip of land near the coast, exposing artifacts from a 15th century Makah community. Log houses, canoes, spears, baskets and other implements of daily life, covered in mud for five hundred years, emerged surprisingly well preserved. A collation of archeologists and tribal members worked to document the cache. For archeologists, a find of this magnitude was a professional high. For tribal members, it was personal. Here was extensive evidence of their ancestors’ lives before Europeans sailed to their shores, before the United States was born, and before disease, treaties and government schools threatened to erase their way of life.

The Makah Cultural & Research Center in Neah Bay offers one of the most thoughtful exhibits I have experienced. Objects are displayed so viewers can understand the role they played in people’s lives, and videos of tribal elders relating the oral history of their people supplement the visual. We wondered about a detail of the canoes on display – why did whale-hunters row with pointed, instead of rounded, oars? The attendant explained that pointed oars leave fewer drips, giving hunters the advantage of stealth, really important when hunting by canoe. Of course!

Most items in the museum were functional – very few were decorative only – but when utilitarian items did incorporate artistic expression, the art was grounded in the essentials of daily life. Even this delicately woven basket shows hunters in a canoe.

We also visited the Seattle Art Museum, where paintings by Aboriginal artists from Australia were on display. The paintings are contemporary, not centuries old, and are meant to be hung on a wall, making them the converse of the Makah objects. (I can hear someone protesting that even decorative art serves a purpose, but that’s a conversation for another time.) Even so, I saw a similar alignment of artistic culture and the needs of survival.

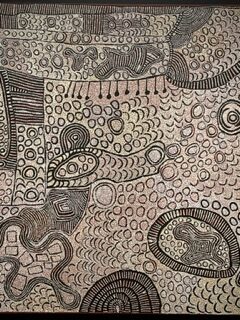

In the painting below, artist Yinarupa Nangala, of the Pintupi people, uses U shapes to represent ancestral women. The women are resting at a rock watering hole after traversing the desert in search of food staples: bush tomatoes and small desert raisins, foods whose shapes also animate the painting. What seems at first blush to be a wholly abstract design is actually the artist’s rendition of the desert landscape where her people have lived, and eaten, for centuries.

Mukulka by Yinarupa Nangala, , 2013

Another landscape by Yukultji Napagati, also of the Pintupi people, is similar in subject matter and even more intricately rendered. This artist also has imagined a group of ancestral women taking a rest while trekking to find food. Look closely and you will see squiggly bends in the lines, indicating the women’s presence in the landscape. Next to where the painting hung on the museum wall, a video played of an aboriginal woman reminiscing about her treks through the desert. She is seated on the desert floor, surrounded by leafy plants of the same yellow tones as in the painting. The artist, I realized, has transported us to the desert where we, as viewers, also crouch among life sustaining plants.

Marrapinti by Yukultji Napangati, 2019

In both museums the work was presented without political justification or fancy aesthetic theory, simply a marriage of ancient culture with the will to survive. For that, the work was all the more compelling.