The Columbia River is wide and powerful and, where it spills into the Pacific Ocean, turbulent. Several miles upstream from the ocean, a cantilevered bridge spans the river. Andrew and I drove across that bridge on our recent trip, and two things amazed us.

One was its length. With a four mile span, it’s the longest continuous truss bridge in North America. And then there’s the upward thrust. We started at the northern end in Washington state where the bridge is low over the water, but as we approached Oregon the bridge angled upward, so steeply that we thought, for an instant, that we were on a draw bridge with a section raised ahead of us. That was impossible, since traffic was flowing, but for a split second we did wonder what we were seeing. Later we learned that the Oregon end of the bridge is 200 feet off the water, high enough for tankers to pass beneath.

We also learned that the river is incredibly tricky. As it nears the coast, the river disgorges massive amounts of sediment which ocean currents sculpt into a sandbar that is four miles wide and six miles long, and constantly changing shape. The result is that this section of the river is one of the most treacherous places in the world for a ship to navigate. To cross the bar, a ship must take on board a Columbia River Bar pilot.

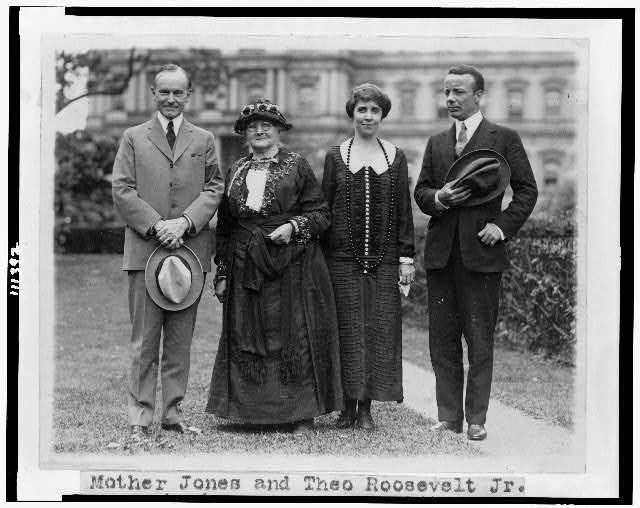

Pilots are highly trained mariners with specialized local knowledge. Typically, they board a ship as it enters or leaves a harbor and guide the vessel either to a dock or to open water. On an inbound trip on the Columbia, a bar pilot will board the ship several miles outside the bar and guide it across before a river pilot boards and takes the ship to various river ports in Washington and Oregon. Bar pilots began operating in 1846, some forty years after the Lewis and Clark expedition made camp near Astoria, Oregon. One hundred and fifty years later, in 1994, Captain Deborah Dempsey moved to Astoria to begin working as a bar pilot.

Bar pilot was Deborah’s last job before she retired, after a long line of “first” achievements. She graduated from Maine Maritime Academy in 1976, the first woman to graduate from any US maritime or military academy. After that, she was the first American woman to be licensed as third, second and chief mate and the first to be a seagoing master. For most of her career she captained commercial ships on journeys around the world, but ultimately decided she didn’t like the down time between assignments. As she wrote in her book, The Captain’s A Woman, “I’ve always wanted to pilot – for masters in my position the natural progression is piloting, handling ships all of the time. Certainly the fun part of being a master on a ship is the ship-handling end of it.”

Navigating the bar is a challenge, but not the biggest one. “The most difficult part about the job – and what the Columbia River Bar pilots are known for – is getting on and off the pilot boat.” Here’s she’s referring to the smaller boat, some 80 feet long, that takes the pilot out to the big ship, where as much as 30 feet of rope ladder has to be climbed to reach the deck. Conditions can be difficult – in her book Deborah describes working in 24 foot swells, 65 knot winds, low visibility and pouring rain.

Most tellingly, when she advanced to captain’s rank, she embraced the responsibility. “You want to do it right, better than anybody else has done it before you.” She tamped down her emotions. On tough days, “you try not to show anybody your emotions. At times you have to go to your quarters, shut the door, and let loose.” Regrettably, she doesn’t say what she did to loosen up. But she does commend her crew. “Help makes the difference. If you have good help, it’s fun. . . You don’t want to make captain, then forget what it was like to be the mate and think everybody’s there to wait on you.”

In the end, I think her most telling comment is this: “It’s fun to be the boss.” Clearly, she was confident about her skills and experience, and not shy about using them. The fact that most women don’t captain ships, or escort tankers across the Columbia River bar, was beside the point. She had set her sights on a goal that was right for her, and she wanted to achieve at the highest level.

When I talk to book clubs and library groups about the women in my book, a frequent question is what can we do to help girls and young women chart a satisfying path for themselves, as Deborah did for herself. I don’t pretend to have all the answers and I’d love to know what you think. Thank you for any suggestions you send my way.

_____________________

To celebrate Women’s History Month, I will be talking about my book at the Brookline Public Library on March 7 and at the Boston Public Library on March 8. Links to register for the events are on the Events page of this website. I hope to see you at one of these wonderful libraries.