November 2021

Yesterday I voted in Boston’s mayoral election where there were two candidates, both women. A little more than a century ago, this could not have happened — neither me in the voting booth nor women on the ballot. Upstate New York had a lot to do with making it possible.

My husband and I recently took a road trip through upstate New York. Our original impetus was to see the Erie Canal. Ever since grade school, when my class sang a song about the canal, I’ve had a vague, romantic notion about mules pulling boats along the canal. The mules are long gone, and the boats are for tourists, but we had a great time learning history.

The canal was an outstanding feat of engineering for its time, or any time. With only hand tools and animal power, laborers dug a ditch 40 feet wide and 363 miles long to create a waterway that linked Albany to Buffalo. Engineers crafted a system of 83 locks that raised and lowered the water level so boats could be loaded, weighed, navigated and brought into drydock for repair. Once the canal opened in 1825, local farmers and small manufacturers could ship goods east on the canal and south on the Hudson River, all the way to New York City, or west to the Great Lakes and Canada. The tremendous burst of canal-fueled commerce brought new people to the area – immigrants, religious zealots, utopian pioneers, abolitionists and women’s rights activists. Some, such as freedom seekers escaping slavery, passed through on their way to Canada.

To recapture some of that animating spirit, we visited the canal towns of Auburn and Seneca Falls. Auburn was home to Harriet Tubman, who settled there after the Civil War. It’s also where William Seward launched his political career, becoming governor, senator, Secretary of State under Abraham Lincoln, and the skilled negotiator who purchased Alaska for the country. Frances Seward was a woman’s rights activist and abolitionist who opened her kitchen to travelers on the Underground Railroad. In her recent book The Agitators, Dorothy Wickenden highlights Frances’s life, along with that of Harriet Tubman and Martha Coffin Wright, another women’s rights activist.

After touring both the Tubman house and the Seward house, I came away with a sense that history unfolds as a Rube Goldberg device. Activate one thing and another part of the contraption springs to life which, in turn, pushes some other button. Unless you’re Rube himself, you can’t predict exactly what the path will be, but with hindsight we can see that certain events sparked a chain reaction. In this case, the canal’s opening triggered a jump in political and social activism. Frederick Douglass, for example, lived in Rochester, partly because it was close to the canal and the railroad, which made his frequent travels possible. He was part of a community of free Blacks who, together with other like-minded people, were vocal supporters of abolition.

The abolitionist cause, in turn, was linked to the fight for women’s rights. Though many women were members of abolitionist groups, they were barred from full participation. In 1840, Lucretia Mott and Elizabeth Cady Stanton went to London for the anti-slavery convention, but they were consigned to an upstairs gallery and not allowed to speak publicly. Stung by such treatment, they resolved to launch a women’s rights convention. Eight years later they did just that in Seneca Falls, with Lucretia Mott as a keynote speaker. The convention issued the now-famous Declaration of Sentiments, and the fight for suffrage was on.

In Seneca Falls, we visited the Women’s Rights National Historic Park where the visitors’ center is chock-a-block with reminders of what women’s legal status once was. No right to own property, no right to enter into a contract, no right to retain her earnings if she was married, no right to make decisions about her children. Female suffrage emerged as a priority, but it was hardly the only injustice women faced, many of which continued well into the 20th century.

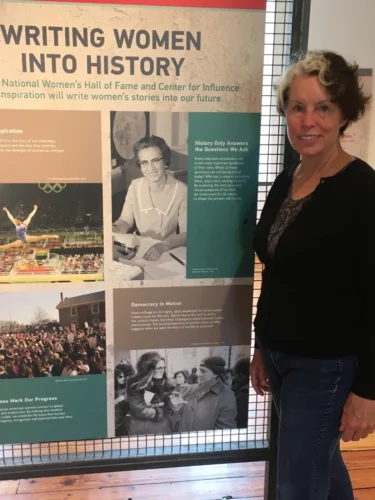

The Women’s National Hall of Fame, near the park, occupies an old limestone building that was once a knitting mill, with big windows and original wood floors. Located between the canal and a railway line, the mill was well positioned to transport goods. In this case, the good shipped were woolen products because the abolitionist mill owners refused to work with Southern grown cotton.

Recent scholarship has focused, rightly and belatedly, on the sidelining of Black women in the fight for female suffrage. The topic is worthy of a PhD dissertation, far more than I can cover here. Instead, I’ll return to the Rube Goldberg analogy.

Before the canal opened, some of the pieces for progress were already in place. Religious groups were taking bold positions. Free Black communities flourished. Emma Willard, a pioneer in women’s education, set up a school for girls. Politicians like DeWitt Clinton promoted a forward-looking agenda. The canal, though, boosted commerce and travel to entirely new levels and facilitated the movement of people and exchange of ideas. When the Civil War came, the canal and its offshoots carried food and materials across the northern states and territories, without involving the Mississippi River. Did the canal directly affect the cause of women’s rights? I can’t honestly answer that question. But what I can say is that the canal, so sleepy looking in the picture above, contributed to a vigorous political and social dialogue which, in turn, led to my vote yesterday.

* * *

In book related news, I submitted the final proofs to my publisher, with fingers crossed that I caught all the typos. I’m now getting blurbs from other authors and look forward to sharing them with you soon. My book is listed on Goodreads and Amazon, and soon I will be contacting independent book stores to be sure they also stock my book. If you have a favorite bookstore to recommend, I’d love to hear from you. More news next month!