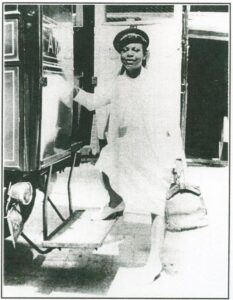

Susan Smith was born in 1847 into a farming family that raised pork in Weeksville, a section of Brooklyn, New York sandwiched between Bedford-Stuyvesant, Brownsville and Crown Heights.

Her nine siblings became school teachers and principals, but she went into medicine, graduating as valedictorian from New York Medical College for Women in 1870. When she arrived at Bellevue Hospital for clinical training, the men greeted her and the other women with hisses and spit balls.

The medical field was a far cry from what we know today. Germ theory was not widely accepted, disease was rampant and racial segregation in health care was endemic. Yet, within those parameters, she established several medical clinics and specialized in neonatal care, childhood disease and childhood malnutrition.

She also married the Reverend William McKinney and became mother to two children.

Did I mention that Dr. McKinney was Black, with a mixed lineage of African, Shinnecock Indian and European ancestors? The institution of slavery was robust when she was growing up. Lee surrendered at Appomattox only five years before she began medical school and when she graduated, the Fifteenth Amendment was ratified, giving “citizens” the right to vote without regard to color. As everyone knew, the word “citizen” in that context meant men.

Not content only to practice medicine, Dr. McKinney turned her attention to issues of concern to Black Americans and all women. She was a co-founder of the Women’s Loyal Union of Afro Americans, an organization dedicated to fighting lynching, and a member of the Equal Suffrage League of Brooklyn.

After Reverend McKinney died, she married a US Army chaplain by the name of Steward, and traveled with him to western outposts, earning medical licenses in Montana and Wyoming. In 1906 they moved to Wilberforce University, an historically black school in Ohio, where she became campus physician.

I learned about Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward when I interviewed Dr. Muriel Petioni for my book, They Called Us Girls. Known as the “mother of medicine in Harlem,” Muriel grew up and practiced medicine in Harlem. The only woman in her medical school class in 1937, she worked in the South during the Jim Crow era. By the 1960s, when civil rights legislation passed Congress and landmark decisions emerged from the courts, she was back in Harlem.

I learned about Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward when I interviewed Dr. Muriel Petioni for my book, They Called Us Girls. Known as the “mother of medicine in Harlem,” Muriel grew up and practiced medicine in Harlem. The only woman in her medical school class in 1937, she worked in the South during the Jim Crow era. By the 1960s, when civil rights legislation passed Congress and landmark decisions emerged from the courts, she was back in Harlem.

In the 1970s, when institutions began hiring Black doctors, she founded a robust referral network for Black women doctors, and named the group the Dr. Susan Smith McKinney Steward Medical Society.

Like the organization’s namesake, Muriel understood her work was far more than dispensing medical advice. She worked in the schools, advocated for public health, helped invigorate Harlem Hospital and was active in national organizations that invested in Black women and girls. Her vision of the work she was called to do was as broad as Dr. McKinney Smith’s was of hers, waypoints on the road to fuller opportunity.

_________

Remember the photo in last month’s newsletter, of women wading in the ocean? Several of you commented on their clothing and I have an update from my friend Alicia Kennedy, professor of fashion history. The women are wearing shirtwaists, all the rage in the late 1800s, because the style allowed freer movement. Sometimes women paired the shirtwaist with a tie, maybe because the style was borrowed from men’s clothing, or possibly to signal that women were determined to break from expectations.

The women in the picture also wore jaunty caps. One friend speculated that the caps and ties signified membership in a women’s temperance group. Such groups were indeed popular, and Dr. McKinney Steward belonged to one, but I’m not sure that that sartorial flourish signified disapproval of cocktails.