Vaccines are all the buzz these days. Saturated with news coverage, we’ve absorbed new terms like spike protein and messenger RNA, and learned that some vaccines, like Pfizer-BioNTech’s and Moderna’s, are really a new breed. Without recent advances in biotechnology, we wouldn’t have these vaccines at all.

Did you know that the polio vaccine, which rolled out in the 1950s, also relied on a seminal advance in biotechnology? Neither did I, not until I interviewed Dr. Martha Lepow for my book, They Called Us Girls.

The polio vaccine, both the Salk and the Sabin version, use a tried-and-true method – inoculation with a small dose of virus to stimulate an immune response. The problem, before the breakthrough that I’ll explain in a minute, was that there was no feasible way to produce enough virus to test, and eventually to inoculate, all the children who were at risk. For the clinical trials alone, over a million schoolchildren in several countries were to be inoculated with the Salk vaccine. If and when the vaccine was approved, a country-wide and then a world-wide campaign would require unprecedented amounts of virus.

Traditionally, virus was grown in mice and monkeys, which meant production was limited. Labs needed ample facilities to house animals, and it was an expensive undertaking. Scientists tried to find another way to cultivate virus, and in 1949 they succeeded. Three doctors working at Children’s Hospital in Boston invented a method to cultivate virus in tissue samples, not whole animals, which greatly sped up the process and reduced the expense. When one of the three doctors moved to Cleveland, Ohio, he set up a “virus lab” at City Hospital where he met Martha Lepow, then a resident in pediatrics.

Martha thrived with one-on-one patient care, but when asked to work in the lab, she said yes. There, she conducted research, used the new method to grow virus and, when the Salk trials began, tested patient samples for evidence of antibodies. On the day the lab’s director learned that he and his colleagues had won the Nobel Prize for their work, she was there to celebrate. As she told me, “I would characterize the work in the lab as one of the biggest advances in medicine in the second half of the twentieth century, right up there with the development of penicillin.”

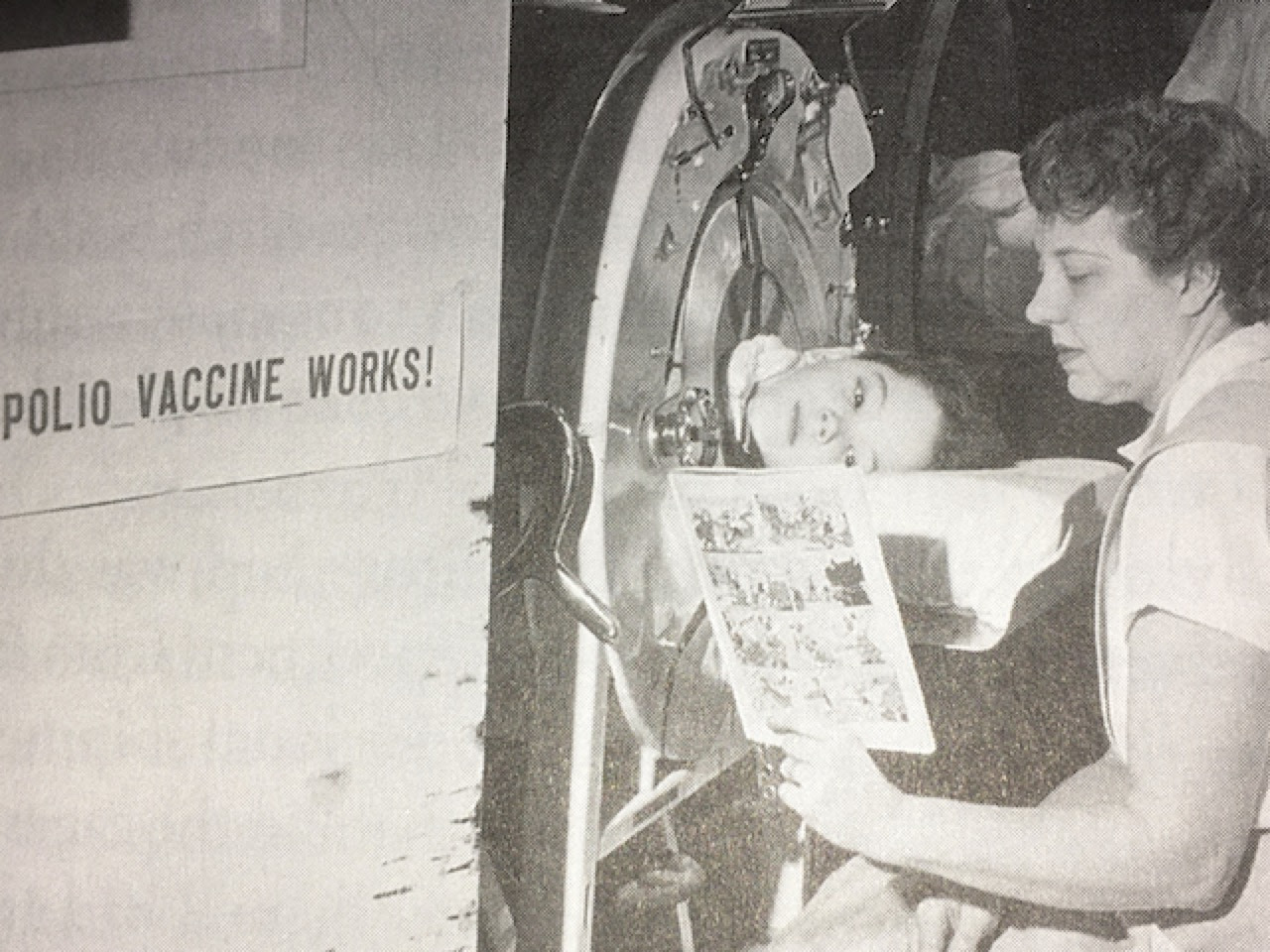

Here, Martha reads to a young polio patient. The picture was taken right after April 12, 1955, the day the Salk vaccine was declared effective. For this girl, the vaccine came too late. The virus had so severely damaged the muscles in her chest that she could no longer breathe on her own. She was confined to a tank respirator, commonly known as an “iron lung.”

Martha went on to become one of the nation’s foremost experts on pediatric infectious disease. She won many honors and accolades throughout her career, but always preferred spending time with patients where even something small, like reading aloud, could bring relief to a sick child. You’ll read more about Martha’s decision to become a doctor when They Called Us Girls comes out next year.

~ ~ ~

Speaking of vaccines, after I sent you the book’s introductory chapter, I realized I had failed to correct a typo. My excuse (if you can call it that) is that I was in a daze from having had the second Moderna shot. Twenty-four hours later, when I felt normal again, I was elated to think we might soon be able to see one another in person.

PLEASE EMAIL ME WITH YOUR COMMENTS

They Called Us Girls is a collective biography of seven women who pursued professional ambitions in the mid-twentieth century, an era when women were expected to stay home. The book will be published by Cynren Press in the spring of 2022. Find out about my upcoming book.