January 2022

I saw Sam Adams’s baby quilt the other day. I was at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston to see the quilt exhibition, on what was my first public outing since having surgery to repair a ruptured tendon in my hand. By the time you read this, I expect to be out of the cast and doing rehab exercises, on my way back to two-handed typing and two-handed piano scales. Meanwhile, my surprising take-away from the quilt exhibition is that fabric can tell a story of American history. (The quilt shown above is Vote by Irene Williams of Gee’s Bend, AL, 1975.)

The delicacy of the floral pattern on the Adams baby quilt is surpassed only by the delicacy of the embroidery, stitched by Sam’s mother in 1703, when she herself was just a girl. Baby Sam was baptized in this quilt, as were his 11 siblings. Because he grew up to play a leading role in the American Revolution, sign the Declaration of Independence and serve as governor of Massachusetts, the blanket takes on the luster of history. At the very least, it gives insight into one family’s domestic life in 18th century America.

Before Sam Adams’s mother took a stitch, an unknown seamstress living in the colony known as New Spain embroidered fantastical animal figures onto a deep red bedcover. The fact that the bedcover resembles a European tapestry is hardly a coincidence. By the 1600s, Spain was well on its way to establishing a colony, headquartered in Mexico City, that covered much of the southwestern United States, as well as Central America and South America. That’s a reminder. Like quilts and blankets, the history of America is composed of many strands.

unidentified maker

Nineteenth-century seamstresses used Civil War imagery and material in their work. In one quilt, General Ulysses S. Grant is shown in silhouette astride a rearing horse, an image of victory crafted from fabric that was salvaged from Army uniforms and bed rolls. In another, a Diné (Navajo) woman wove a blanket for an Army major stationed in Santa Fe in the late 1860s. During the Civil War, residents of what was then the territory of New Mexico were divided in their loyalties. The Union Army ultimately prevailed at a pivotal battle in the northern part of the territory. But if it had not, and if the Confederates had controlled the southwest and the Pacific coast, there would have been no U.S. Army installation in Santa Fe and no woven blanket. At least not this one. History indeed hangs by a thread.

Post-Civil War, Harriet Powers created a sparkling story quilt, then a popular genre. Her Bible Quilt was publicly displayed at numerous fairs in Georgia, where she had once been enslaved and, in 1895, President Grover Cleveland saw it when he visited the “Negro Building” at the Cotton States and International Exposition in Atlanta. Her appliquéd and piece-worked panels tell the story of her life, complete with farm animals and religious experiences. She also depicts a meteor shower that occurred in 1833, four years before she was born, but which so profoundly affected those who saw it that it became legendary.

More recently, a quilt called Strange Fruit II portrays a violent side of Black American life. Carolyn L. Mazloomi is both an aeronautical engineer and a historian of African-American quilts. She draws on Billie Holiday’s song title to pay tribute to the victims of lynching.

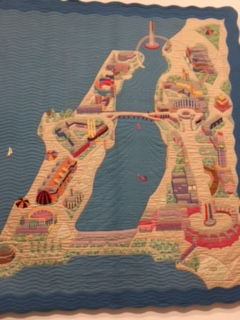

An aerial view of Chicago nestled into Lake Michigan appears on a prize-winning quilt from the Century of Progress Exposition held in Chicago in 1933. The surprising twist is that it was crafted by an architectural draftsman named Richard Rowley. He entered the contest using his mother’s name, to avoid what surely would have been an adverse reaction to a male quilter. He felt bound by assumptions about the kind of work men and women were each expected to do, but his actual accomplishment reveals just how erroneous assumptions can be. He provides a mirror image of the women in my book.

Richard H. Rowley and probably Louise Rowley

* * *

In book news, the manuscript is headed to the printer. Barring paper shortages or other supply chain problems, the book will be in stores in March, in time to celebrate Women’s History Month. But you can pre-order now directly from the publisher. https://www.cynren.com/catalog/they-called-us-girls.

I will close by saying thank you for reading this newsletter and letting me know what’s on your mind. I hope your new year is the best it can be.